From Congo To South Africa With (Rumba) Love

For an artist with deep Congolese roots and proud cultural immersion, the inspiration of Rumba in an art show is not only a form of personal expression but a connection to other Africans who have embraced the dynamic ‘Rumbaism.’

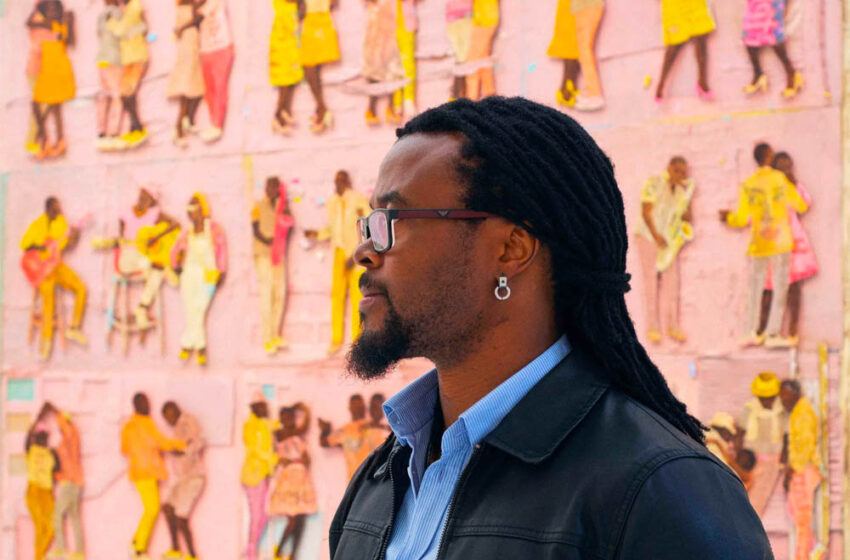

“Rumba is part of my DNA. I was born and grew up in Congo [where] Rumba is our music, and I cannot escape from it; so as an African-based artist, I want to portray the continent positively, and Rumba allows me to do that,” explained Johannesburg-based Congolese visual artist, Thonton Kabeya.

Known for his work on “African cosmopolitanism” and his three-dimensional canvas constructions which involve glueing layers of canvas together that are cut, carved and sculpted before painting, Kabeya has excelled in this debut solo exhibition at the Everard Read, where he is now signed.

The Everard Read Gallery, Africa’s oldest commercial gallery, stands at the heart of Johannesburg. An iconic establishment since its establishment in 1913, it has distinguished itself as a centre for South African art.

And there would not have been a better choice for Kabeya to showcase and celebrate one of Africa’s best-known music beats and dance genres.

Dubbed Pasada, a Spanish word that means to pass or turn, the exhibition depicts and captures the Rumba beat to which dance partners synchronise their step-by-step movements, by making space for each other.

The fractal, bold yellow Tablet Series I, a large-scale painting, depicts a sequence of Rumba scenes.

The atmosphere oozes the energy, passion, colour, style, and creativity of the dominant Rumba theme that reflects Kaybeya’s experiences in dance clubs in Congo.

“The inception of my work often starts with an idea, an observation, and from there, I start thinking about how to develop the observations and ideas into something tangible,” Kabeya said.

According to UNESCO, Rumba has its roots in the ‘Nkumba’ dance, from the ancient central African Kingdom of Kongo (now Angola, the Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

‘Nkumba’ as it was known before being fused with jazz and evolved into modern-day Rumba, was a unique cultural identity, a binding spiritual and emotional glue for Africans who were taken into slavery in the Americas.

Some of its latter-day prolific producers and promoters include Franco Lumabo Makiadi (also known as the “Sorcerer of the Guitar”), Tabu Ley Rochereau, Papa Wemba, and Koffi Olomide.

Kabeya’s body of work is presented in three series; the Pasada, the Moziki Street, and the Tablet. They are all related since they capture the realities of people who live in places such as Congo, Angola, Senegal, and Cuba.

The Tablet series is a pictorial representation of contemporary African cities and is painted as both representational and abstract, while the Pasada series depicts Rumba dancers in moments of connection. The Moziki Street series captures the social dynamics in and around a Rumba club, including street life.

According to the artist, “the series focuses on simple activities like interacting with one another by dancing, [and] by chatting, etc.”

Kabeya has developed a distinctive technique that explores and experiments with new ways of creating texture, colour and depth – and challenges his medium of paint and canvas.

“I developed my technique over time, and I’m still evolving skills-wise as an artist; my studio is like a laboratory where I try different materials and concepts,” Kabeya explained.

Tracing his artistic journey, Kabeya put his success down to mentorship and constant experimentation.

“I never became an artist; I think I was born one [and] the journey is just a process to impose your name as an artist to the art world.”

Judging from the facial expressions of the people viewing Kabeya’s work at the Everard Read the work also offered a very direct encounter with some of the artist’s lived experiences.

bird story agency